China’s Xi Mimics Mao’s Crisis Response in Sweeping Indoctrination Drive

‘Spiritual baptism’ campaign comes as Chinese leader sustains damage from pandemic, economy, U.S. tensions

Chun Han WongMay 21, 2023 at 10:00 am ET

SINGAPORE—Chinese leader Xi Jinping is taking a page out of Mao Zedong’s crisis playbook to contain the damage caused by the tumultuous final months of his zero-tolerance Covid controls.

In recent months, Xi has launched indoctrination drives, including a mass-study campaign to propagate his political doctrine. The campaign has swept through schools, hospitals, banks, courts, police stations, military bases and places of worship in what he describes as a “spiritual baptism” for all members of the Communist Party.

To deliver on its mission of rejuvenating the Chinese nation, “the entire party must unify its thinking, unify its will and unify its actions,” Xi told officials at an April meeting.

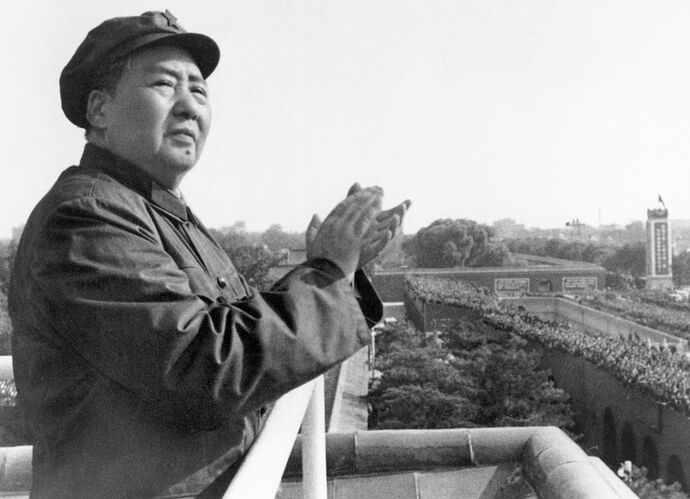

In parallel, Xi has commanded officials at every level to conduct on-the-ground “investigation and research,” echoing a program that Mao directed in the early 1960s in what historians say was an attempt to shift blame for the disastrous consequences of the Great Leap Forward.

Mao Zedong used an ‘investigation and research’ program as a way to shift blame for the Great Famine that resulted from his plans to industrialize China, historians say. Photo: Bettmann Archive

The fervor of Xi’s campaigns reflects the extent to which recent events have battered the Chinese leader’s image, said Wu Qiang, an independent political analyst in Beijing. Xi’s aim, he said, is “reassert control over public narratives and mask his failings.”

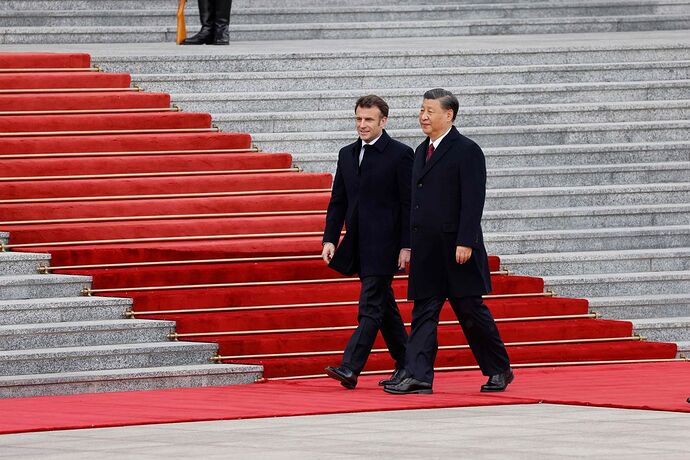

Outwardly, Xi projects strength. Last fall, he took a norm-breaking third term as party leader and maneuvered close allies into virtually every significant position of power. Since ordering an end to Covid controls late last year, he has met face-to-face with a parade of world leaders, including Russia’s Vladimir Putin and France’s Emmanuel Macron, while brokering a surprise detentebetween Saudi Arabia and Iran.

But Xi also faces significant challenges. Nationwide protests against his Covid policies in November pointed to a fraying of public trust, while an abrupt pivot away from “zero Covid” measures led to untold deaths. China’s economy, meanwhile, has labored to shake its pandemic hangover, a task made harder by intensifying tensions with the U.S.

Unease over China’s shifting political and business climate under Xi, including state-led efforts to fan a personality cult around him, has pushed more Chinese—particularly well-heeled ones—into moving abroad.

3:42

0:00 / 8:02

China has slowly claimed and militarized disputed territory across the South China Sea, often at the expense of its neighbors. WSJ explains the economic repercussions for the U.S. and countries across the Indo-Pacific.

Xi has directed indoctrination drives in the past, but few were pursued with such scale while hearkening so directly to the Mao era.

The latest campaigns kicked off in noteworthy fashion in late March, when the party leadership issued a directive encouraging “investigation and research,” or diaocha yanjiu, whereby officials personally go out into the field on fact-finding missions to improve policy. The directive urged officials to “seek truth from facts” across broad areas that Xi has demanded action on—including economic security, environmental protection and efforts to shape a more egalitarian China through “common prosperity.”

Xi’s directive directly echoed Mao’s 1961 campaign calling on cadres to investigate and research problems, which he launched during the Great Famine that resulted from his radical plans to rapidly industrialize China.

Historians say Mao used “investigation and research” as a vehicle for rectifying policy errors and shielding himself from criticism, as the campaign implied that lower-level officials were poorly informed about realities on the ground and therefore at fault for misgovernance.

“Without investigation, one has no right to speak; without investigation, one has no authority to make decisions,” the March directive said quoting Xi, who was invoking a Mao slogan. State media recounted how Xi, since his days as a local and regional administrator, had frequently toured the grass-roots to hear directly from ordinary people.

Xi touring a wheat field in north China’s Hebei Province earlier this month. Photo: Yin Bogu/Zuma Press

Like Mao’s effort, Xi’s “investigation and research” campaign is “an indirect acknowledgment of having mucked up and a promise to fix errors and do better,” said Timothy Cheek, a professor and China historian at the University of British Columbia. However, given the vast changes in Chinese society since the Mao era, “I’m not convinced Xi’s efforts to rectify will fly with important sections of Chinese society from urban professionals, to intellectuals to military folk,” Cheek said.

The second phase of the campaign came in April, when the Chinese leader ordered senior officials to prepare a new “themed education” program to infuse “Xi Jinping Thought” into the minds of cadres from Beijing all the way down to the country’s more than 2,800 county-level areas.

The party leadership has left little to chance, dispatching 58 “guidance” teams across China to steer the study campaign. By mid-April, all regional governments on the Chinese mainland, roughly 120 central party and state agencies, as well as more than 70 major state companies and financial institutions had launched programs for propagating Xi Jinping Thought, according to the official Xinhua News Agency.

Party publishers released new anthologies of Xi’s remarks for use as political textbooks. State companies and universities staged cultural performances and poetry contests to promote Xi’s ideas with a dash of artistic flair. Authorities in the northeastern city of Harbin promised to keep marriage registries open on an auspicious Saturday in May, a gesture local state media described as a way to honor Xi’s political philosophy.

At one study session in mid-April, more than a dozen party members at a small-town hospital in the southeastern province of Jiangxi toured a local revolutionary site, according to an official account. Participants wore party flag pins and read aloud passages from Xi’s speeches and the party’s governing charter. They also recited the party’s admission oath, which all members swear when they first join.

“We in the new era must treasure the crimson banners that our revolutionary forefathers dyed red with their blood,” one participant said in sharing what he learned from the session.

Newsletter Sign-up

The 10-Point.

A personal, guided tour to the best scoops and stories every day in The Wall Street Journal.

“It is, of course, uncertain to what extent these efforts are effective in boosting confidence in the regime,” said Maria Repnikova, an expert on Chinese media and propaganda at Georgia State University. “But the very participation in this campaign symbolically legitimizes Xi Jinping and his mode of governance.”

As with past education campaigns, participants in the latest study sessions are typically required to jot down the insights and lessons they gleaned into notebooks, which are then submitted to higher-ups for review. On Zhihu, a popular question-and-answer website, some users posted template essays that others can use as a guide for crafting their own.

In a recent issue, a party-run magazine documented what it called “first signs of distortion” in Xi’s push for more on-the-ground research, quoting officials complaining that their superiors have passed the buck by delegating research tasks to lower-ranked bureaucrats.

Such campaigns generally devolve into “formalism,” or box-ticking behavior that gives priority to form over substance. But Xi’s latest effort could still yield positive outcomes if it spurs officials into tackling socioeconomic issues they previously ignored, said Deng Yuwen, a U.S.-based political commentator and former editor at the Study Times, a newspaper published by Beijing’s elite Central Party School.

“The ultimate goal is to uphold Xi’s leadership status,” Deng said. “If you closely follow Xi Jinping, and closely follow his ideas and his policies, you’ll pass the test.”

Xi has met face-to-face with several world leaders this year, including France’s Emmanuel Macron. Photo: ludovic marin/Agence France-Presse/Getty Images

Write to Chun Han Wong at [email protected]