Clues to the U.S.-Dutch-Japanese Semiconductor Export Controls Deal Are Hiding in Plain Sight

Photo: MANDEL NGAN/AFP/Getty Images

Report by Gregory C. Allen and Emily Benson

Published March 1, 2023

On October 7, 2022, the Biden administration upended more than two decades of U.S. trade policy toward China when it issued sweeping new regulations on U.S. exports to China of advanced artificial intelligence (AI) and semiconductor technology. These export controls were designed after consultation with key U.S. allies, but the United States originally implemented them unilaterally.

This was a major diplomatic gamble.

In the face of rapidly advancing Chinese AI and semiconductor capabilities, the United States wanted to move fast, so it was willing to take the risk of moving first alone. The United States has the strongest overall position in the global semiconductor industry, and it was by itself strong enough to reshape the Chinese semiconductor industry in the short term. Over the medium to long term, however, this move could have backfired disastrously if other countries, particularly Japan and the Netherlands, moved to fill the gaps in the Chinese market that the partial U.S. exit left.

But that is not going to happen. In late January 2023, the Biden administration’s gamble paid off when the United States secured a deal with both the Netherlands and Japan to join in the new semiconductor export controls. Some officials suggested to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) that the result of the dialogues is better characterized as an “understanding” rather than a formal deal, as some details have yet to be worked out. Regardless, the United States has secured the top three international partners needed to ensure the policy’s success. Taiwan had already made a public announcement that it would support enforcement of the October 7 regulation’s application of the U.S. Foreign Direct Product (FDP) rule.

However, the exact contours of the deal with the Netherlands and Japan are not yet publicly known. China has aggressively usedtrade restrictions in the past as a coercive and punitive tool of foreign policy, and all parties to the deal remain tight-lipped, likely in the hopes that this will diminish China’s appetite for retaliation. No doubt the White House would love to have had a big photo-op signing ceremony to show how its gamble on allied diplomacy paid off, but the Biden administration has remained remarkably leak-proof on the topic. The lack of leaks is happening for the same reason the administration was able to pull the deal off: they take allies’ concerns—including a desire for secrecy—seriously.

Thus, journalists and semiconductor companies have struggled in vain over the past few weeks to gain clarity on the elements of the deal. The full details are unlikely to be known until the Dutch and Japanese governments publish their updated export controls regulations, which will take months. In the case of Dutch export controls, some types of policy changes might never be published at all, such as changing the policy for reviewing certain types of export license applications from “case by case” to “presumption of denial.”

In the meantime, however, there are plenty of clues to the deal’s contents from a careful analysis of three elements: (1) the role that Dutch and Japanese companies play in the global semiconductor value chain, (2) the revealed policy preferences of the Biden administration based on the content of the October 7 regulations, and (3) the nature of the underlying legal authorities that constitute the Dutch export controls system. This paper addresses each in turn.

The Role of Dutch and Japanese Companies in the Global Semiconductor Value Chain

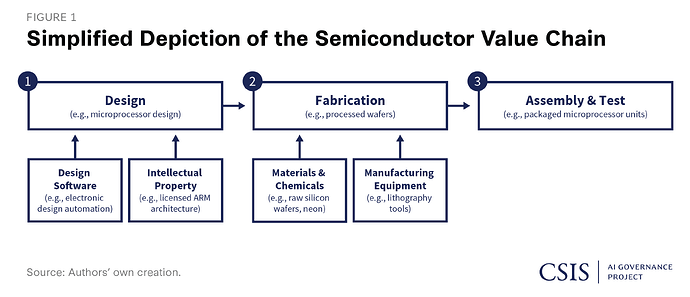

The semiconductor value chain includes three major segments: chip design, fabrication (i.e., chip wafer manufacturing), and assembly and testing. See Figure 1 for a simplified depiction.

Image

The United States has the strongest overall position in the global semiconductor industry, but that is as a leader of a deeply interwoven multinational value chain in which other countries also play critical roles and possess technological capabilities that are extremely difficult to replace. The October 7 export controls restricted U.S. sales across multiple segments of the value chain, but the lynchpin of the entire policy is the fact that U.S. semiconductor manufacturing equipment is an essential part of nearly every single Chinese chip factory. There are multiple categories of equipment—such as deposition, etching, and process control—in which U.S. companies are either exclusive or dominant suppliers, and China’s domestic semiconductor equipment industry is tiny and generally far behind that of the United States. The regulations identified 11 specific types of advanced semiconductor equipment (equipment that is only used for producing advanced chips) where there is no foreign substitute for U.S. technology. Some of these equipment types are among the most complicated and precise machines used anywhere in the global economy. Each represents an extremely tall technology mountain that China must climb to reach its goal of a self-sufficient semiconductor industry.

The United States moved first for two reasons: First, to move fast. Chinese chip companies were purchasing equipment as quickly as they could in anticipation of future export controls. Second, the United States wanted to prove that it was not going to ask allies to bear any costs that it was unwilling to bear itself. The long-term success of the policy required multilateral cooperation, most urgently from the Netherlands and Japan.

The Biden administration correctly assessed that the United States was, by itself, strong enough to reshape the Chinese semiconductor industry in the short term. However, Dutch and Japanese companies possess advanced technological capabilities in highly related disciplines. Whereas it would have likely taken China, by itself, decades to replace the equipment that the United States is no longer willing to sell, assistance from the Netherlands or Japan could have had China back up and running in as little as a year or two.

The global semiconductor manufacturing equipment industry has seen ever-increasing market consolidation as the cost and complexity of remaining competitive at the state of the art has soared. For the equipment categories in which the United States is dominant, Dutch and Japanese companies have increasingly found head-to-head competition with U.S. firms unattractive. It would have taken Dutch and Japanese companies billions or tens of billions of dollars in research and development (R&D) costs to produce products that might capture only meager and highly unprofitable market share. However, the October 7 export controls could have changed that calculus. With U.S. companies prohibited from competing in the large and growing Chinese market, Dutch and Japanese companies might have found monopoly access to China attractive enough to justify the equipment R&D expense for new product lines to replace U.S. ones. Once successfully established in China, Dutch and Japanese companies might have been in a position to more effectively compete with and displace U.S. firms in these market niches around the world.

Whereas it would have likely taken China, by itself, decades to replace the equipment that the United States is no longer willing to sell, assistance from the Netherlands or Japan could have had China back up and running in as little as a year or two.